What the shifting evidence on the coronavirus means for school re-openings in South Africa

Note: This article was originally published on the Daily Maverick on May 10, 2020.

The quality of education is one area where South Africa has seen an encouraging upward trend over the last twenty or so years, according to internationally quality-assured data. The Covid-19 pandemic will have an impact on this trend, but this does not have to be large or enduring.

Learners in South Africa need to be in school. Remote schooling is mostly impossible for the poor in developing countries. Currently, the technology and human capacity are simply inadequate. Moreover, 80% of South Africa learners receive publicly funded meals at schools, in a context where even before the pandemic, 11% of learners were in households which experienced hunger at some point in the year. This last statistic does not differ much by age.

During this pandemic, it can be said the thinking on school closures has been through three phases.

First, in an almost automatic response based largely on past experiences with influenza (flu) pandemics, schools were quickly closed. This response was especially strong in developing countries, given their worse capacity to deal with a surge in intensive care patients.

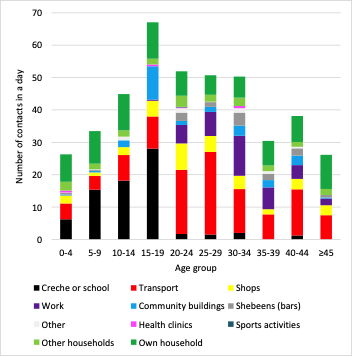

The data behind the strong focus on schools by health experts is illustrated in this graph, which reflects a widely used 2012 South African sample.

If one closes schools, one reduces substantially the contacts made by young people, defined here as others they talk to and touch. Moreover, much transport activity is related to moving to and from school. Yet contacts made during walking, which two-thirds of our learners do, are likely to be lower than those made in taxis and buses, used by 23% of learners.

In a second phase of the thinking, it became accepted that very few children were becoming ill with Covid-19. This led the idea of ‘kids-as-walking-virus-bombs’. Children would infect each other at school, and from there older household members, though one would have almost no idea who was spreading the virus because children were not showing symptoms. This understanding implied that school closures were necessary.

However, in a third phase, it is becoming clear that not only do children rarely show symptoms, they also seldom contract or transmit the virus. This changes the rationale for school closures substantially. There are now several reviews of the medical literature dealing with transmissions by children, and the evidence points strongly to children as exceptionally low transmitters.

However, why this would be so is not well understood, and experts are still concerned about noteworthy contradictions in the findings across some studies.

From a school policy perspective, it is not enough to know children are less likely to infect others. Age-specific statistics are needed. Among the studies currently available, and new ones are being released on a daily basis, a study from Iceland provides some guidance. This study found that one per cent of the population aged over 20 tested positive for the virus, no children under ten tested positive, and around 0.4% of adolescents aged 10 to 19 tested positive. Iceland is currently the only country with infection statistics for the population as a whole.

Research into what actually happened to infections when schools were closed, or not closed, is at an early stage, as one requires significant historical data for this. Such research must take a holistic view. For instance, if children locked out of schools are instead mixing with each other and various adults in their community, then this would greatly reduce any health benefits of school closures.

A pioneering study has found that school closures played an especially weak role in reducing Covid-19 cases across twenty rich countries, relative to other measures such as travel restrictions and workplace closures.

Sweden is just one of two countries never to have closed primary schools, which go up to grade nine in that country. The Swedish government claims to have found no above-average infections among teachers who continued working at these schools. This would be in line with the idea of children as weak transmitters of the virus.

It is critical that the debates leading up to the re-opening of South Africa’s schools, and the actual process of re-opening, which will almost certainly occur in stages, be informed by the emerging medical evidence and reports on best school practices. Citizens who understand what is known, and what is not known about the virus are more likely to support evidence-driven policies and embrace the necessary behavioural changes.

Re-opening the pre-school sector, covering around 2.4 million children, and the earliest school grades, seems least risky in terms of infections. Moreover, there are strong educational and nutritional arguments which favour prioritising these levels.

It appears social distancing in schools is especially important for older learners, who are more likely to transmit the virus. By Grade 12, a third of learners are aged 20 or older. In a way this is fortunate, as more mature learners are more likely to exercise the necessary restraint.

The greater mixing among secondary learners due to subject teaching probably accounts for the higher levels of contacts in the above graph for youths aged 15 to 19. Secondary schools would have to strive to keep groups of learners in specific classrooms, without mixing these groups, while teachers move from class to class.

It appears the greatest risk may lie with those learners who are old enough to be significant transmitters of the virus, yet too young to be good at social distancing. Whether this middle group is substantial should become clear in the coming weeks and months, as more age-specific data emerges. It is critical that we monitor the emerging research, evaluate it carefully, and communicate the essential findings in ways that reach everyone.