This article was originally published on News24 on 20/02/2021

Machine learning has promised a wide range of improvements ranging from lower crime due to more effective police patrolling and longer lives with precision medicine. Captivated by data science’s giant leaps ahead, it is easy to forget those left behind. The uncounted, the unsurveyed, the undocumented and unresearched have many different faces but often include materially poor communities, socially marginalised individuals such as migrants and the homeless, and residents in war-torn areas. Over the coming years, this divide between the seen and unseen may grow even deeper and wider as societies become increasingly reliant on data for decision-making.

Such a dynamic can have at least three undesirable pathways: Firstly, if all goes according to the machine learning masterplan countries that have good information systems will earn a large social dividend, becoming more efficient and well run, which would work in the direction of further increasing global inequality. Secondly, if the customization of systems and policies is increasingly reliant on big data sets, then these systems and policies would reflect the characteristics and preferences of those who are surveyed and documented, not taking account of the characteristics and preferences of those missing from the data sets. But even more concerning perhaps, is the risk that a greater reliance on data will erase many uncounted at-risk countries and vulnerable groups from global policy dialogues, advocacy campaigns and aid prioritisation decisions. In this funding environment, it has become very difficult to attract funding for your cause without a headline-grabbing statistic, or at least a clear sense of the parameters and size of the problem. Following the economic crisis, there is less money to go around, but that may pass. However, the focus on transparency and improved monitoring and evaluation is likely to sharpen over the next few years and this could effectively deprioritize many sectors where impact is harder to measure over a short period and communities where the quantification of impact is challenging due to for instance their remote location, language difficulties or lack of local measurement and data gathering skills. Because you need money and resources to generate reliable data, there is also a bias against informality and smallness.

In Economics, we often invoke the streetlight effect to illustrate the problem by focusing on the problems that are easiest to solve. As the story goes, a policeman encounters a drunk man searching for his car keys under a street light and help him with his search. Then, after a while of searching without any luck, the policeman asks the drunk man if he is sure that he lost keys here. He then explains that he lost the keys in a park far from there but he is searching for the keys under the street light because this is where the light is and he can see clearly.

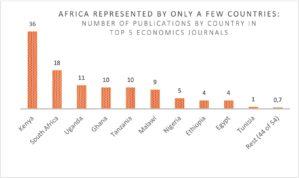

Note: Based on data from Porteus, O. (2020), Research Deserts and Oases: Evidence from 27 Thousand Economics Journal Articles on Africa. Preprint.

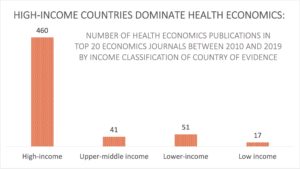

Sifting through all 27 000 Economics articles about Africa published over the past two decades, Obie Porteous from Middlebury College in the US found most researchers were looking for their keys in the patch of sidewalk lit by the streetlight. The research was not evenly spread across the continent’s 54 countries. Instead, it was dominated by five countries, namely South Africa, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, and Malawi. The 2020 study found that five countries accounted for 45% of the articles on African countries in Economics journals and 65% of the articles on African countries in the top 5 Economics journals, even though these countries represented only 16% of the overall population of all African countries. By contrast, seven countries – Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia and Guinea – also represent 16% of the African continent’s population but was the focus of only 3.5% of all articles on African countries in Economics journals. When exploring the reason for this bias, the author cited factors related to country-specific cost and benefits related to data gathering — including the number of annual tourist visits to the country, violence and safety and having English as an official language — as the main explanation. Similarly, Kalle Hirvonen from the International Food Policy Research Institute in Addis Ababa’s 2020 study reports that there were more articles published in the top two health economics journals over the past decade about the Nordic countries with a combined population of 27 million people than about African or Asian countries, which represents 2.9 billion of the world’s people.

More generally, it is known that household surveys systematically exclude or undercount vulnerable populations – including homeless people, prisoners, hospital patients, nomadic groups and informal housing dwellers. Admittedly, the omissions and undercounting are not intentional and these are difficult groups to survey. Roy Car-Hill from York University estimated that these missed individuals amount to 4% of the world’s total population but as much as one-fifth of the world’s poorest quintile. Because of the overrepresentation of the poor and the vulnerable, these exclusions and underestimates will materially affect estimates of need such as access to clean water or adequate sanitation.

Note: Country of evidence is the country that is studied and described by the publication. The list of top 20 Economics journals was based on the ranking of IDEAS/Repec. The Journal of Economic Literature (JEL) codes were used to identify health economics articles published in Top-20 Econ and J of Dev Econ. The graph is based on data from Hirvonen, 2020, This is US: Geography of evidence in top health economics journals. Health Economics Letters, Volume 29, Issue 10: p. 1316-1323

Data availability tends to mirror the existing inequalities in our global system. Therefore, a greater reliance on data could further widen these inequalities if not accompanied by enhanced vigilance. Innovations such as image processing of satellite images or aerial photographs have helped generate knowledge and research about under-surveyed areas. And researchers have become more imaginative and savvy about gathering data with new approaches such as citizen science or with alternative modalities such as phone interviews or Whatsapp when it is unsafe or prohibitively expensive or too time-consuming to use fieldworkers to do in-person surveys. But in the long-term, more coordinated effort will be needed to encourage the research community to pay attention to this problem, including dedicated funding mechanisms which should including funding for data sets but also more broadly support for data literacy and survey skills. The UN has started this process with its 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, calling for a different type of Data Revolution.

Societies cannot allow their tools to determine their destiny. Measurement matters for how societies evolve and thus it is crucial to acknowledge, recognise and measure what we value and care about.