Graphic: Dorothy Kgosi

At the heart of education inequality is the ability to read early on in a child’s life. Ramaphosa, who was the deputy chair of the National Planning Commission when it drew up the National Development Plan (NDP), emphasised the importance of early reading in his 2019 Sona by stating: “Early reading is the basic foundation that determines a child’s educational progress, through school, through higher education and into the workplace.”

All the other investments we make in basic education, and even free higher education for the poor, will not produce the results we want to see unless we ensure that children can read for meaning by the age of 10.

The World Bank refers to the inability to read and understand a basic text by the age of 10 years as “learning poverty”. In work the Research on Socio-Economic Policy (Resep) group at Stellenbosch University has done on reading performance using the Progress in Reading and Literacy Survey (Pirls) data, it was found that 78% of SA children in grade 4 (who would be about 10 years old) could not read for meaning.

That staggering number means large numbers of SA children, most in former black and coloured government schools, are severely disadvantaged because their inability to read for meaning also prevents them from learning well in other subjects such as maths, science and the humanities.

To address learning poverty in SA requires a multi-pronged approach to investment in human capital that begins before birth and recognises the health of parents and children as necessary inputs in inequality-reducing education outcomes. These educational outcomes are crucially dependent on good nutrition; access to quality early childhood development services; access to good quality basic education; quality higher education that offers degrees that are relevant and geared towards knowledge growth and innovation; and accountability frameworks to ensure the resources we spend on human capital inputs deliver the desired outcomes.

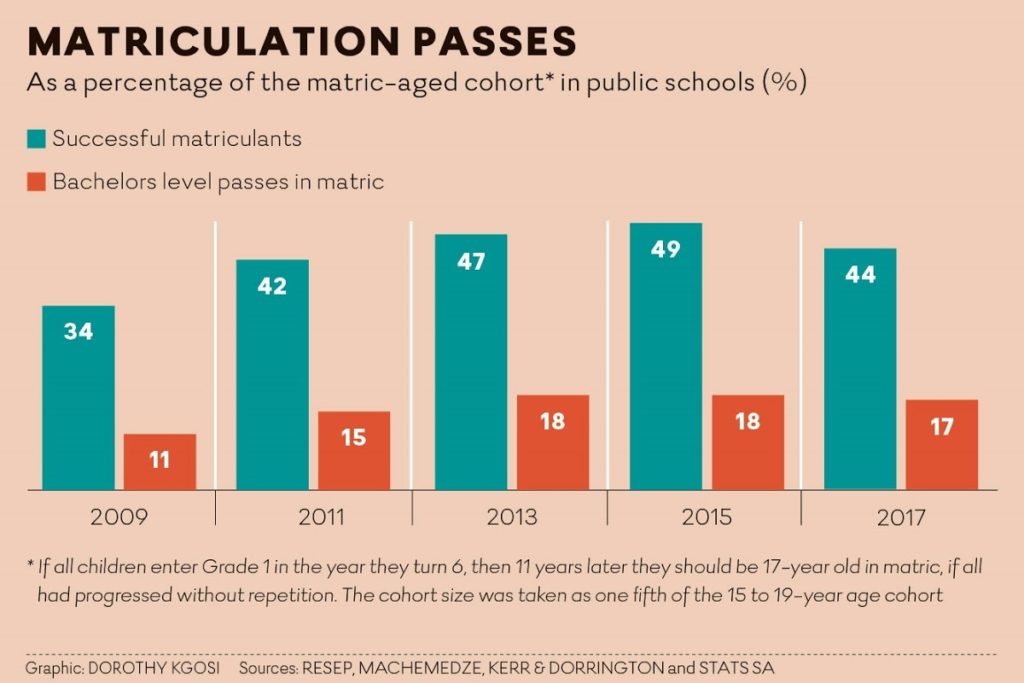

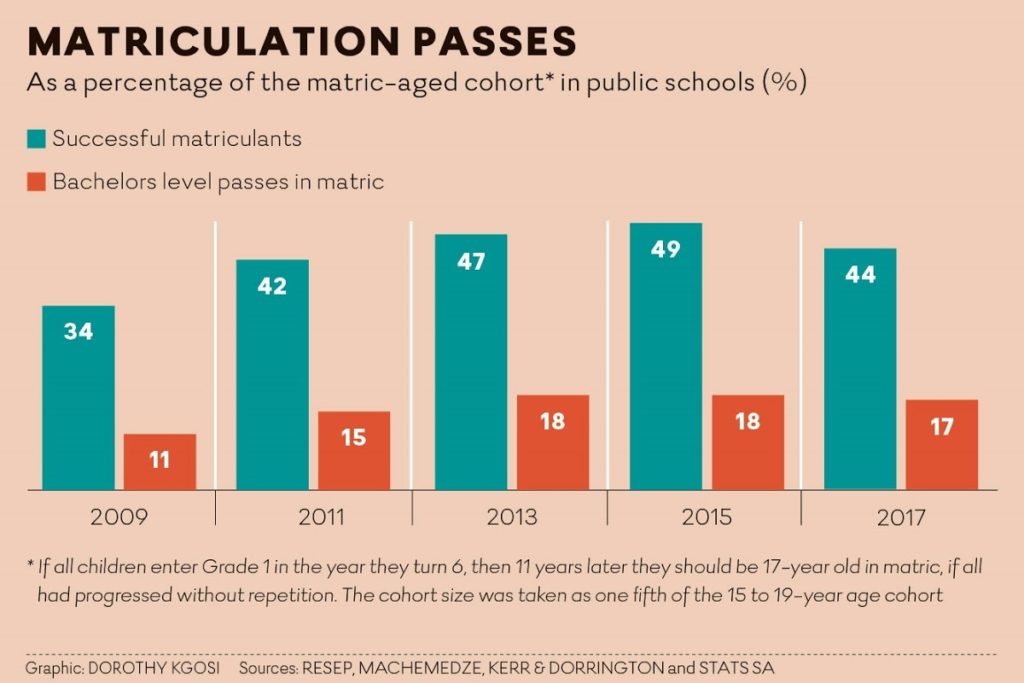

But to eliminate learning poverty we also need to be able to measure it from early on to see what works, long before the final basic education hurdle of matric. It is therefore of critical importance to conduct regular, systemic testing of reading skills among a national sample of learners in early grades to determine whether progress is being made in improving early education quality.

Similar to education, healthcare is also a multi-dimensional issue. The NDP differentiates itself from other health policy documents in emphasising that health is not just a medical issue but determined by a variety of social factors. It is widely acknowledged that the social determinants of health are vital, and that health services contribute relatively little to health outcomes. Education, social development, nutrition, clean water, decent sanitation and adequate housing contribute towards our country’s disease burden and become crucial allies for disease prevention.

The consequence of this broader view is that health is not just the domain of the health department. Greater inter-sectoral and inter-ministerial collaboration is required to address the social determinants of health. However, this does not absolve the health department from its role of providing adequate healthcare.

Health, with its many dimensions, is one of the most difficult outcomes to track. Quality-adjusted life years and disability-adjusted life years may come closest, but require large amounts of data and lack the immediate intuitive connection of well-known health indicators, such as death rates or HIV cases. Deaths, however, are also an imperfect measure of health outcomes as they reflect an extreme health event. It is therefore prone to only flag health issues at a very late stage.

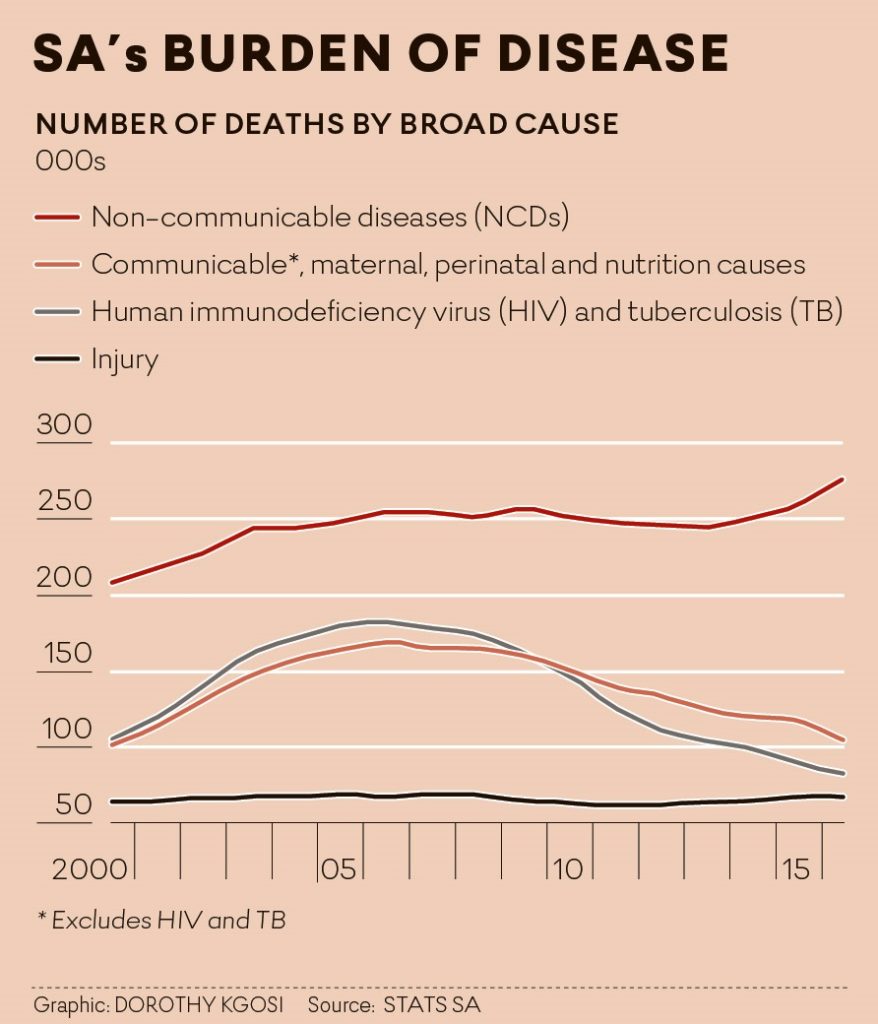

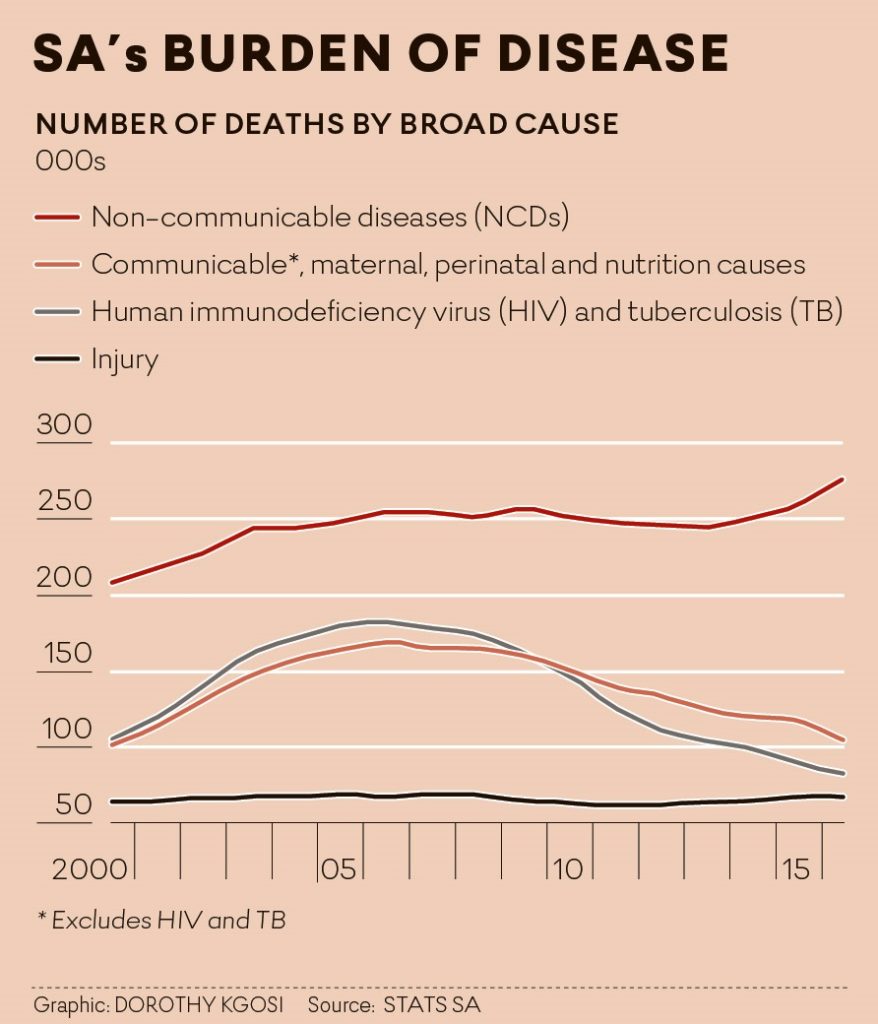

While the state of SA’s healthcare system leaves much to be desired, we have over the past decade become more effective in treating certain causes of death. The number of deaths caused by communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutrition causes, as well as from HIV and TB, have dropped considerably since 2010. Deaths attributed to non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and heart disease are however on the rise, likely attributable to SA’s high and growing levels of obesity.

Graphic: Dorothy Kgosi

The Covid-19 pandemic has illustrated the failures in service delivery and the need for improved quality of care in SA, especially in rural regions. To remedy this situation requires a more equitable geographic allocation of staff, stronger governance, improved performance management and quality measurement, better information systems and the strengthening of patient responsiveness and community accountability.

The NDP’s clarion call to South Africans in 2012 was that it is “Our future — make it work”. For us to make our future work we need to invest heavily in our citizens’ education and health outcomes as early as possible and manage these human capital investments efficiently to ensure that we achieve our goal of societal transformation for the better of all who live in SA.

Banner photo credit: Hush Naidoo